April 2011

When I was 10 years old, my mom took me to see the Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition at the AGO. Like most art-obsessed kids, I was immediately transfixed by these ginormous canvases so blatantly breaking every rule I thought I understood about art. I was having a mental orgasm trying to decode the layers of meaning woven within the art straight from Basquiat’s soul like I was Indiana Jones searching for the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

This little snot-nosed white kid from upper-middle class Toronto was learning about the history of racism, colonialism, rampant unchecked capitalism, etc. likely for the first time in his life because Basquiat brought chaos to an industry once obsessed with order two decades prior.

Basquiat’s art inspired a deep passion for all things radical. It taught me art is only as beautiful as the message and sanctity behind it. I no longer looked at DuChamp’s urinal, or Picasso’s cubes, or Warhol’s soup with a sense of bewilderment. I finally understood them for what they are. RADICAL & REVOLUTIONARY TRIUMPHS OF THE SOUL.

Art became the ultimate symbol of humanity for me. When I had trouble comprehending life wasn’t fair, art reminded me it never was. Whenever I got a little down on myself or my ego got a little too strung out, art levelled me off. I studied it like a religion.

May 2025

Looking at art like a quasi-religious experience is the only way I know how to live life. So, like any passionately religious person, I can’t help but get slightly irritated to borderline irate when the essence of a work of art is manipulated for whatever reason.

We see corporations and governments do it all the time. To stick with the Basquiat theme, here’s Tiffany & Co using an unreleased Basquiat painting to advertise their new diamond necklace:

This painting could’ve been one of the few paintings that changed my and millions of other people’s lives. But nope, some blood diamond company thought it’s better off sitting in their warehouse for 30 years instead.

Boo hoo. I know I sound like the “Monster Energy is Satan” lady we all know and love. But the meaning behind a work of art is important. Stories are how we communicate.

There are good stories and bad stories. Unfortunately, when I go on social media and come across the art that’s so popular there, the majority seems to make up the latter.

I know I know, if Connor McGreggor was reading this he’d probably say something like “Who the fook is this guy???”. wELL aCKcHUALY, I’m OG Bubby Jaustin, Mr. McGreggor. I curated multiple exhibitions for Toronto Metro University, one of the dopest art schools in Canada, bitch.

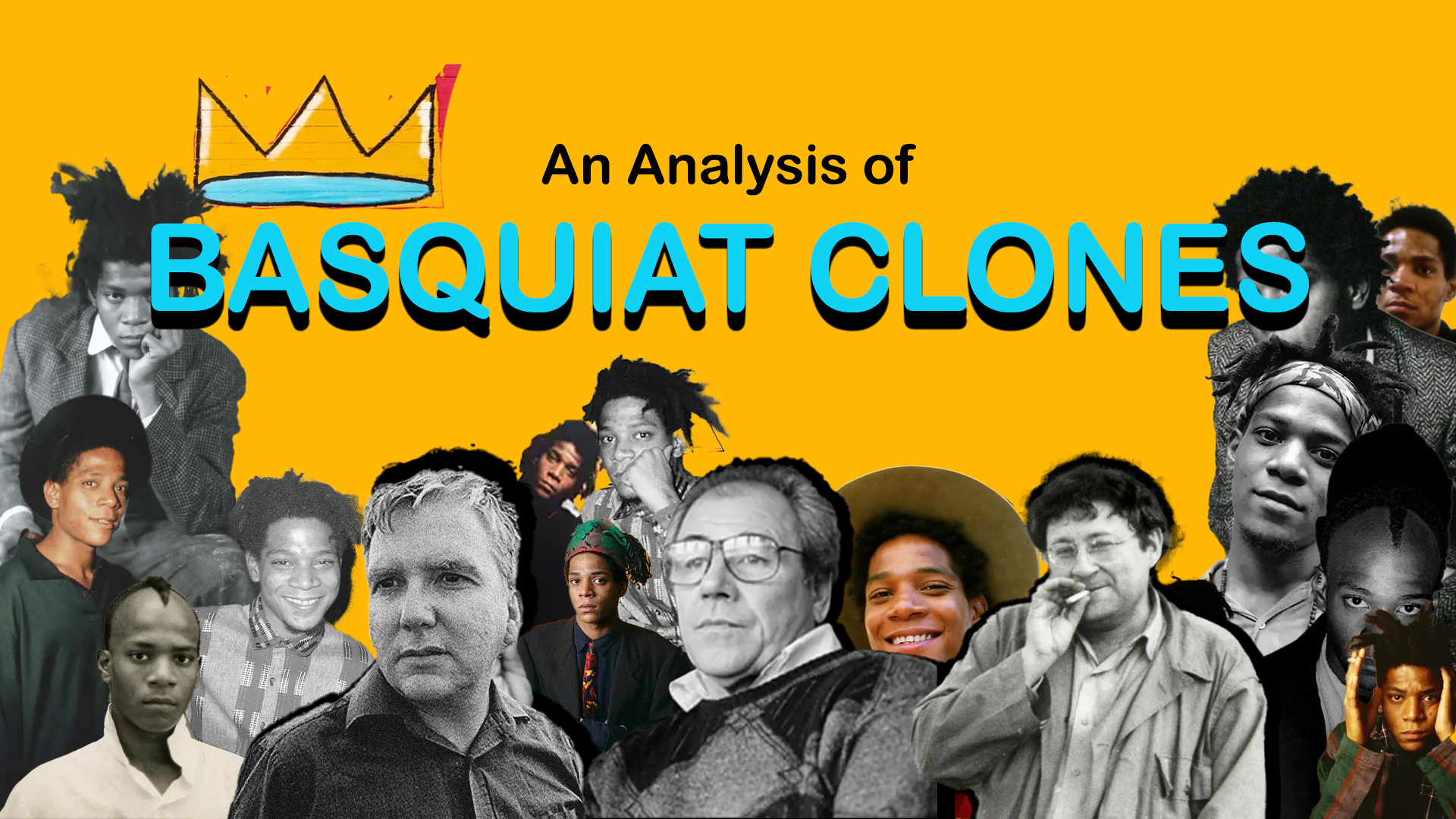

When I talk of bad “storytelling” in the art industry I merely mean redundant storytelling. We’ve all seen it. The 16 year old white kid inspired by Basquiat innocently mimicking the aesthetic with at best zero semblance of substance and at worst ignorantly racist.

Although Social media likes to gang up on these people it’s hard to blame someone who doesn’t know any better. I also can’t blame social media as it’s entirely dependent on aesthetics. Of course a Basquiat or Harring copycat will rise to the top because that’s what’s popular. Radicalism doesn’t reward the algorithm.

So if it’s not the fault of the artist nor of social media, why is it that so many people are copying Basquiat and his contemporaries? Why is the popular art on social media stuck in the past? I can tell you with confidence today’s contemporary galleries aren’t struck by this phenomenon. So why are artists choosing to abide by the algorithm instead of reality???

It took a lot of research but I think I’ve come up with a solution.

The Ghost of Rebellion: Mark Fisher’s Hauntology

“The past cannot be forgotten, the present cannot be remembered”

― Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures

Mark Fisher’s concept of “hauntology” perfectly captures what’s happening with the Basquiat copying phenomenon on social media. For Fisher, our culture is haunted by the ghosts of lost futures—times when artistic rebellion seemed capable of creating genuine change.

Basquiat represents exactly this kind of lost possibility—a moment when art could still shock, disrupt, and manifest something truly new.

When Fisher writes about “the slow cancellation of the future,” he’s describing our current inability to produce cultural forms that don’t reference the past.

ArtTok creators aren’t just copying Basquiat’s aesthetic; they’re grasping for the rebellious energy his work once embodied, an energy that seems increasingly impossible to generate anew in our algorithmically-optimized present.

In “Capitalist Realism,” Fisher argues that capitalism absorbs and neutralizes all resistance to it.

Nothing makes this clearer than watching Basquiat’s anti-establishment art—once a genuine threat to institutional power—transform into a set of recognizable visual tropes perfectly suited for garnering likes and followers.

The radical has been domesticated, commodified, and returned to us as content.

Beyond Reality: Baudrillard’s Simulation

“We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.”

― Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

This brings us to Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra, which helps explain why these Basquiat copies feel so empty despite their technical proficiency.

Baudrillard described four orders of simulation, with the fourth being the most relevant here: representations that bear no relation to any reality whatsoever.

The Basquiat copycats on TikTok exist in this fourth order. They’re not trying to represent Basquiat’s reality or even mask its absence.

Instead, they’ve created a pure hyperreality where the “Basquiat style” circulates as a set of floating signifiers completely divorced from their original context.

The crown motifs that once symbolized Black excellence become mere design elements.

The anatomical diagrams that spoke to the exploitation of Black bodies under capitalism become trendy visual tropes.

As Baudrillard might put it, we’re witnessing the death of the original reference.

When these artists copy Basquiat, they’re not referencing Basquiat himself or the social conditions he was responding to—they’re referencing other copies of Basquiat.

This creates a closed system of reference that spirals further and further from any grounding in lived experience or political urgency.

The Performance of Art: Debord’s Spectacle

“Where the real world changes into simple images, the simple images become real beings and effective motivations of hypnotic behavior.”

― Guy Debord, Society Of The Spectacle

Guy Debord’s concept of the “society of the spectacle” completes our theoretical picture. For Debord, authentic social life is replaced by its representation.

The Basquiat copying phenomenon exemplifies this perfectly. What we’re seeing isn’t art in the traditional sense but the performance of “being an artist” for social media consumption.

Crucially, Debord’s concept of “recuperation” explains how capitalism and mainstream culture absorb and neutralize radical ideas.

TikTok has transformed Basquiat’s anti-establishment art into a trendy, marketable style—”recuperating” its revolutionary potential and rendering it harmless.

The platform doesn’t just distribute these copies; it actively shapes their production through its algorithmic incentives.

The spectacle isn’t just the images being shared but the entire ecosystem around them:

The artist performance videos showing the creation process

The engagement metrics

The comments section debates about authenticity

The merchandise links in bios

Basquiat’s actual art has disappeared, replaced by what Debord would call the “pseudo-world” of representation.

The Cycle of Cultural Recuperation

These three theoretical perspectives combine to reveal a disturbing cycle of cultural recuperation:

Authentic artistic rebellion emerges (Basquiat’s original work)

It gets stripped of its aura through reproduction

These reproductions create a hyperreal simulation (Baudrillard)

The simulation becomes spectacle for consumption (Debord)

The culture becomes haunted by the loss of authentic rebellion (Fisher)

The most important insight from this theoretical synthesis is that social media platforms aren’t neutral spaces where this copying happens to occur—they’re active agents that accelerate and intensify these processes.

TikTok’s algorithm, with its preference for visually striking, immediately recognizable content, creates the perfect environment for the flattening of Basquiat’s multidimensional critique into easily reproducible visual tropes.

What results is a situation where:

Authentic artistic rebellion becomes increasingly difficult (if not impossible)

Copies seem more “real” than originals

Art is valued not for its conceptual depth or political significance but for its ability to generate engagement

The horrifying conclusion is that these Basquiat copies aren’t just aesthetically derivative—they represent the complete inversion of everything Basquiat’s art stood for.

The Broader Implications For Contemporary Art & Culture

This Basquiat copying phenomenon isn’t isolated—it’s emblematic of a broader shift in how art functions in the digital age.

When algorithms determine visibility, authenticity becomes secondary to recognizability.

What we’re witnessing is not just aesthetic mimicry but the collapse of art’s critical function.

As social media platforms reward visual immediacy over conceptual depth, we see similar patterns of flattening across all art forms.

The tragedy isn’t just that Basquiat’s style has been reduced to a template, but that the very possibility of genuinely disruptive art becomes increasingly remote.

What This Means for Artistic Originality in the Digital Age

We find ourselves in a paradoxical moment: never have more people been creating and sharing art, yet never has originality seemed more elusive.

This isn’t about blaming young artists for copying Basquiat—it’s about recognizing the systemic forces that make such copying inevitable.

Perhaps genuine artistic rebellion today means rejecting algorithmic logics altogether—creating work designed to be unshareable, unquantifiable, or invisible to digital metrics.

Or maybe it means creating within these platforms but against their grain, using their tools to expose their limitations.

Whatever form it takes, the next artistic revolution won’t look like Basquiat’s—because it can’t. It will need to find new ways to confront a system that has already incorporated rebellion into its business model.