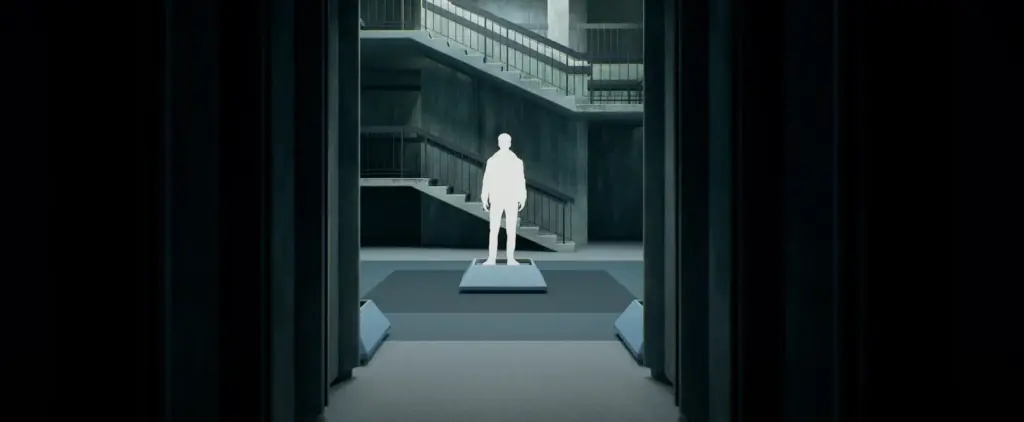

When the elevator doors close and severed Lumon employees transform into their “innies,” we witness the most literal manifestation of Marx’s theory of alienation ever depicted on screen. Apple TV’s “Severance” doesn’t just flirt with Marxist concepts—it takes them to their terrifying logical conclusion.

What Is Marx’s Theory of Alienation and How Does Severance Illustrate It?

Karl Marx’s theory of alienation describes how workers become estranged from their humanity under capitalism. In “Severance,” this alienation isn’t just psychological—it’s surgically enforced. The show provides the perfect lens to understand Marx’s four dimensions of alienation:

1. Alienation from the product of labor

2. Alienation from the act of production

3. Alienation from species-being (human essence)

4. Alienation from other humans

Let’s explore how the show brilliantly illustrates each dimension through its dystopian workplace drama.

Alienation from the Product: What Are the Lumon Employees Actually Making?

In traditional Marxist theory, workers are alienated from the products they create because these products become someone else’s property. In “Severance,” this alienation reaches an extreme.

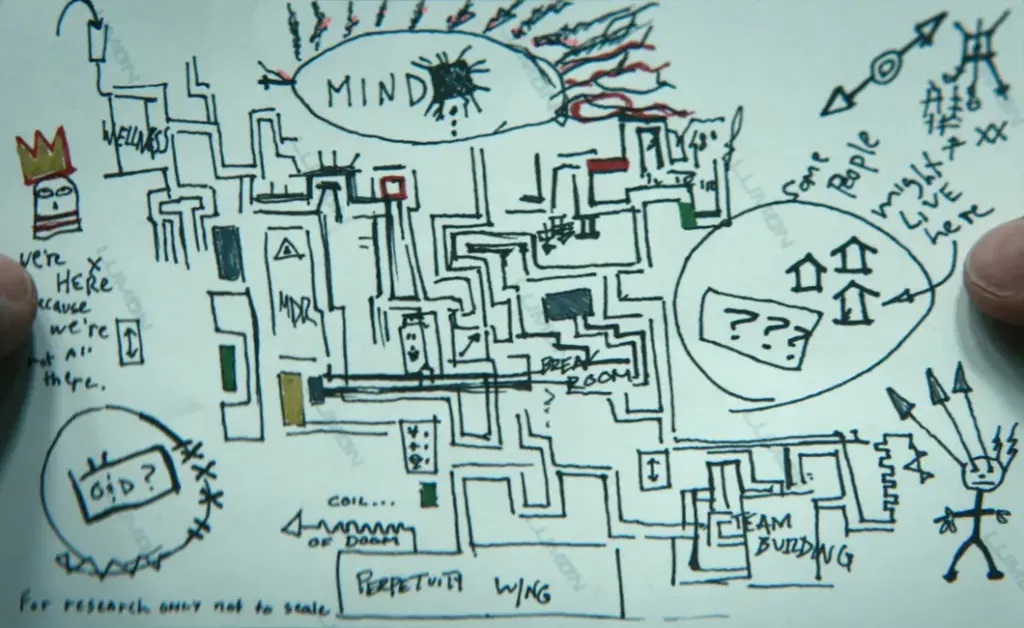

The Macrodata Refinement (MDR) department employees sort “scary numbers” into digital bins with:

No understanding of what these numbers represent

No knowledge of the final product

No comprehension of how their work affects the world

No ownership of what they produce

When Dylan asks, “What do we do here?” Mark can only reply, “We’re refiners. We refine.” This tautological explanation highlights their complete disconnection from their output.

Unlike factory workers who at least see the cars or clothes they make (even if they don’t own them), Lumon’s severed workers exist in a state of complete epistemological alienation. Their work is so abstracted that they can’t even articulate what they’re producing or why.

Alienation from Production: When Work Becomes Your Entire Existence

For Marx, alienation from the act of production occurs when work becomes an external, forced activity rather than a fulfilling expression of creativity. In “Severance,” this alienation becomes literal imprisonment.

The innies experience several extreme forms of production alienation:

Spatial confinement: They cannot leave their workplace—ever

Existential limitation: Their entire consciousness exists solely within Lumon’s walls

Temporal totality: They have no existence outside of working hours

Procedural absurdity: They perform tasks based on how numbers “feel,” a process they can’t explain

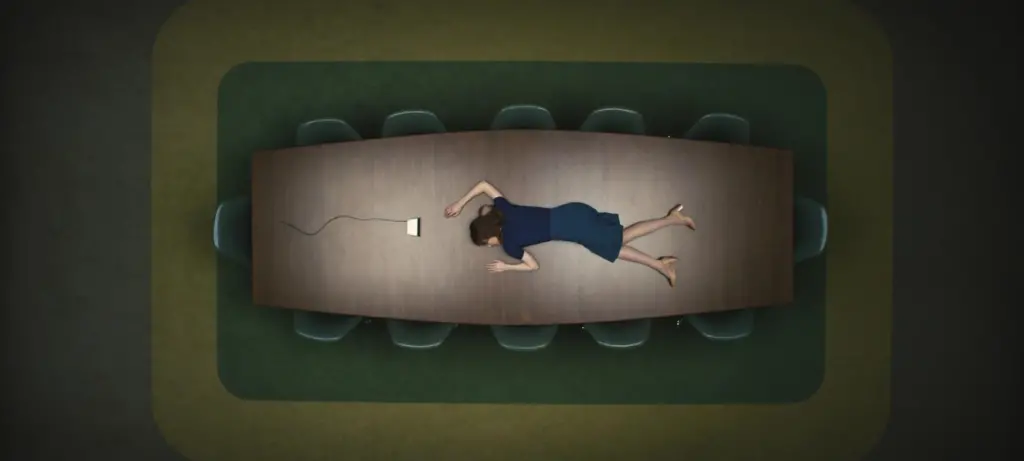

The severed workers don’t just work at Lumon—they only exist at Lumon. They have no life outside work because, for them, there is no outside. When Helly attempts suicide rather than return to work, she embodies the extreme of this alienation—preferring non-existence to continued labor under these conditions.

Alienation from Human Essence: The Severed Self

The most profound innovation of “Severance” is its literal severing of consciousness, creating the ultimate form of alienation from what Marx called “species-being”—our essential nature as creative, social beings who find fulfillment through meaningful work and community.

The severance procedure creates workers who are alienated from:

Personal history and identity

Family relationships and friendships

Creative expression and leisure

All context for their existence

When Irving discovers an outie life filled with painting—creative expression completely absent from his innie experience—we see this alienation in stark relief. His fundamental human essence, his creative nature, has been surgically removed from his work self.

This alienation is doubly tragic because the innies intuitively sense something is missing. As Dylan poignantly asks after glimpsing his outie’s child: “I have a fucking kid? And I don’t get to be with them?” He grasps that his humanity has been stolen to make him a more efficient worker.

Alienation from Others: Corporate Division by Design

Marx’s fourth dimension of alienation involves separation from other human beings. Capitalism transforms social relationships into market relationships, fostering competition rather than cooperation.

In “Severance,” Lumon deliberately manufactures division through:

Departmental segregation: Workers are physically separated

Induced paranoia: Departments are taught to fear each other

Regulated interaction: Social contact is strictly controlled

Prohibited fraternization: “Romantic fraternization” and “excessive discussion of personal lives” are forbidden

The “perpetuity wing” with its cult-like worship of Kier Eagan codifies this division as corporate dogma. The four “tempers” (woe, frolic, dread, malice) are kept separate in Kier’s mythology just as the departments are kept separate in the office layout.

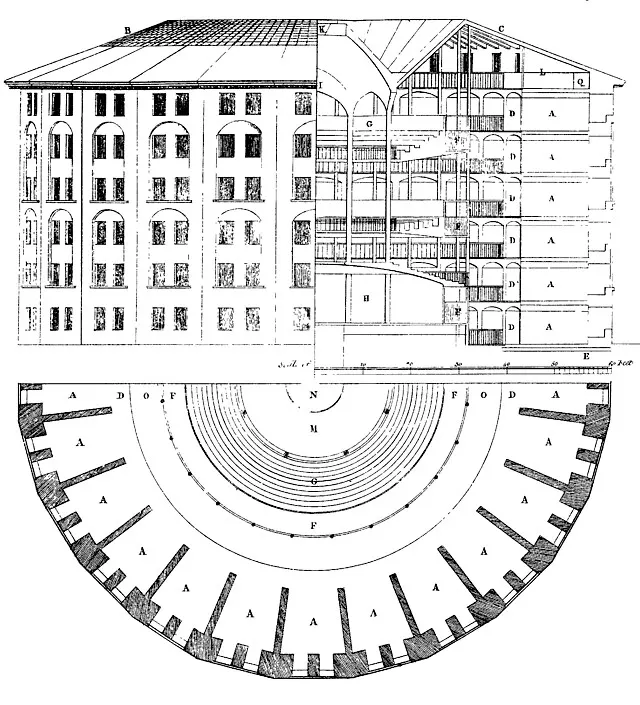

The Corporate Panopticon: Surveillance and Self-Policing

Building on Marx’s theory of alienation, Michel Foucault’s concept of the panopticon helps us understand how Lumon maintains control. In “Severance,” surveillance takes multiple forms:

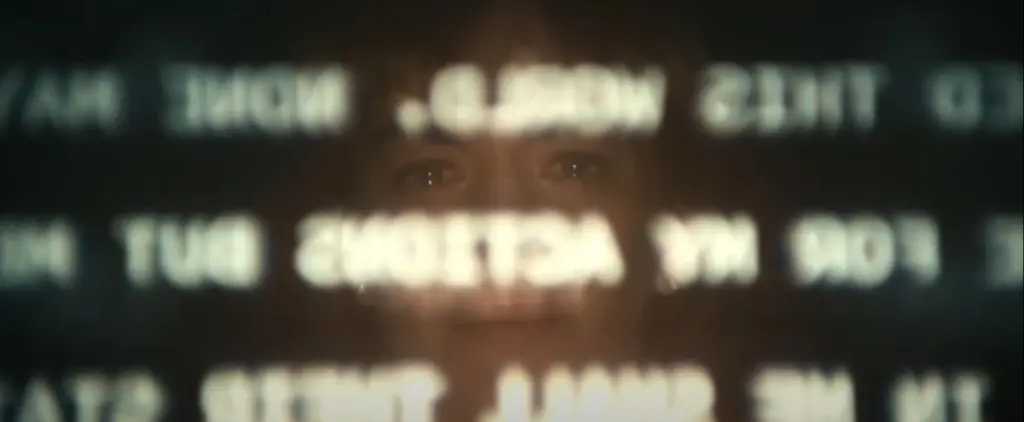

Physical surveillance: Cameras and monitoring by management

Psychological surveillance: Break room “reintegration” sessions

Self-surveillance: Innies policing themselves, knowing outies may disapprove

When Dylan gains temporary consciousness in his outie life and discovers he has a son, it creates what we might call a bifurcated panopticon. His outie self becomes both jailer and judge, making decisions that his innie self must live with but cannot influence.

This surveillance extends to the most intimate possession—their own bodies. The innies are alienated from their physical selves, which become vessels temporarily occupied before being reclaimed by the outies at 5 PM.

Resistance Through Community: Finding Humanity in Connection

Despite this extreme alienation, the severed workers find ways to resist. Their rebellion emerges not through traditional labor organizing but through reclaiming their humanity through connection.

Key forms of resistance include:

Building relationships: Irving and Burt’s connection challenges departmental division

Sharing information: Mark and Helly’s mutual support and knowledge exchange

Creating meaning: Dylan’s obsession with perks and office trinkets

Asserting identity: Collective efforts to discover who they are beyond work

When Mark tells Helly, “The point is, we’re not just livestock. We’re people,” he articulates their fundamental resistance—a demand for recognition of personhood despite being created solely for labor.

The Break Room: Ideological Reprogramming and Total Control

The “break room” scenes represent perhaps the most disturbing extension of Marx’s theory. When Helly is forced to repeat “I am sorry for the trouble I have caused” until she genuinely “feels it,” we witness alienation from one’s own emotions and moral autonomy.

This goes beyond Marx’s concept of alienation and enters territory explored by later Marxist theorists:

Repressive desublimation: The channeling of desires into forms that reinforce control

Ideological state apparatuses: Institutions that indoctrinate subjects into dominant ideologies

Hegemonic consent: The manufacturing of agreement to one’s own exploitation

Lumon doesn’t just want the innies’ labor; it wants their complete psychological submission.

Consciousness as Commodity: The Ultimate Capitalist Frontier

“Severance” shows us that the final frontier of capitalism is not just the commodification of labor but the commodification of consciousness itself. The outies sell not just their time or skills but fragments of their very existence.

This represents what Marxist theorist Mark Fisher might call consciousness as commodity—the ultimate extension of capitalist logic, where subjective experience becomes a resource to be exploited, fragmented, and sold.

When Dylan tells his colleagues, “We’re not just parts of the whole; we are the whole,” he rejects this commodification. He asserts that the innies are not mere labor fragments but complete persons deserving of agency and self-determination.

What Can Severance Teach Us About Modern Work?

“Severance” doesn’t just illustrate Marx’s theory of alienation—it radically extends it for our contemporary moment. The show suggests that in our rush to compartmentalize work from life, we risk severing ourselves from our own humanity.

The series resonates because it reflects trends already in motion:

Work-life integration: The blurring of boundaries between professional and personal

Digital presenteeism: The expectation to be always available

Identity fragmentation: Maintaining different personas across contexts

Surveillance capitalism: The monitoring and commodification of human experience

Frequently Asked Questions About Marxist Themes in Severance

How does the severance procedure relate to Marx’s concept of alienation?

The severance procedure physically enforces the separation that Marx saw happening psychologically under capitalism. By literally splitting consciousness, it creates workers who experience the ultimate form of alienation—from their very selves.

What would Marx think of the “work-life balance” that severance claims to provide?

Marx would likely view the “work-life balance” promised by severance as the ultimate capitalist deception. Rather than truly balancing work and life, it completely subordinates one fragment of consciousness to labor while allowing another to believe it’s free.

How does Severance critique modern corporate culture?

The show critiques modern corporate culture by exposing its underlying logic: that workers are valued only for their productivity, not their humanity. The meaningless perks, corporate jargon, and wellness initiatives at Lumon parallel contemporary workplaces that offer superficial benefits while demanding ever more from employees.

What does Helly’s rebellion symbolize from a Marxist perspective?

Helly’s rebellion represents class consciousness—the awareness of one’s exploitation that Marx saw as necessary for revolutionary change. Her refusal to accept her condition, despite having no memory of choosing it, symbolizes the inherent human drive toward freedom and self-determination.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Question of Personhood Under Capitalism

The brilliance of “Severance” lies in how it transforms abstract Marxist theory into visceral human drama. By literalizing alienation through the severance procedure, the show forces us to confront fundamental questions about work, identity, and freedom.

As Helly desperately writes to her outie: “I’m a person. You can’t do this to me.” That plea articulates the essential struggle against alienation in all its forms. It’s not just a worker demanding better conditions; it’s a consciousness demanding the right to exist beyond its utility as labor.

In our increasingly fragmented, work-dominated world, “Severance” reminds us that Marx’s 175-year-old theory of alienation remains eerily relevant. Perhaps more than ever, we need to question systems that treat human beings as resources to be optimized rather than persons to be fulfilled.

What aspects of Marx’s theory of alienation do you see in your own work experience? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Interested in more philosophical analyses of popular media? Check out our articles on The Greatest Concert You’ve Never Heard and Matt Johnson’s “Blackberry” as Modern Canadian History